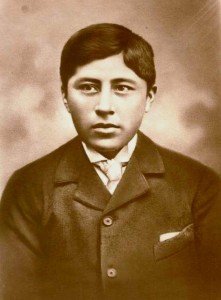

Dorothy Day

Died: November 29, 1980

Cause for Canonization: Servant of God

There are people all around us every day who live saintly lives. Some of them may even be called “saint” in the future by the Church. Dorothy Day was a woman who, much like Saint Teresa of Calcutta, was sometimes called a saint in her work.

Dorothy was born in Brooklyn, NY, in 1897. The family moved to San Francisco and then Chicago, where they lived in poorer housing after Dorothy’s father lost his job. Even though Dorothy was young, she knew what it was like to feel shame over one’s living conditions. As a youngster she loved to read inspiring stories of people who did good things in the world.

She attended college in Illinois but dropped out to take a job as a newspaper reporter in New York. The paper she worked for operated under the belief that all property and possessions should be owned by communities, not by individual persons, so that through sharing, there was always enough for everyone to live on. She joined groups of people protesting the United States’ involvement in World War I and joined groups that rallied for women in the U.S. to be able to vote in elections.

Her family had attended services at an Episcopal church, but Dorothy was drawn to the Catholic faith and attended Mass in New York, Chicago, and New Orleans when she worked in those cities as a reporter. When her daughter was born in 1927, Dorothy felt sure it was important to have her baptized and give her a Catholic upbringing, and she formally joined the Catholic Church.

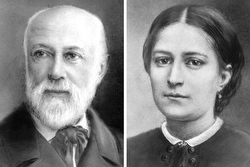

Working as a reporter for Catholic magazines in New York, she prayed to the Blessed Mother to help her to use her talents to help the working poor. She soon met a man named Peter Maurin who told her to use her journalism skills to start a newspaper that could educate people about the teaching of the Catholic Church and how they related to social justice for people. Her kitchen table in her Greenwich Village apartment became her office, and she sold the paper, The Catholic Worker, for a penny a copy so that almost anyone could buy and read it.

When word began to travel about the things Dorothy wrote, people who didn’t have enough food or a place to live began to come to her for help. Her apartment became a place where people could stay when they had nowhere else to go.

Eventually, Dorothy and others at her newspaper began to lease apartments and houses and even farms where people could go to stay. These were known then, and are still today, as Catholic Worker houses. When the Depression hit, a lot of people needed this help.

Not everyone liked Dorothy or agreed with her, especially when she wrote again and again in the paper that war was wrong and the U.S. should not be involved. During World War II, some of the young men who worked for the paper or in houses refused to fight in the military and were either sent to prison or served as medics—without weapons—in the war.

Dorothy and other members of the Catholic Worker movement protested against nuclear weapons and were arrested many times for this. She also believed in equal rights for persons of all colors and backgrounds and took part in civil rights demonstrations in the late 1950s. She was in danger at times and was even shot at in Georgia.

Pope Paul VI invited her to receive communion from him in Rome in 1967, a sign of honor for her work. When she became too ill to travel, Dorothy was visited by people like Mother Teresa of Calcutta, who gave a her a cross usually worn only by her order’s Sisters.

She died in 1980. During her life when people called her a saint, Dorothy did not like the term. However, the effort began in 1983 to have her canonized, and Pope John Paul II gave the Archdiocese of New York permission in 2000 to open the cause for sainthood.

Connecting to Be My Disciples®

Grade 3, chapter 20

Grade 4, chapter 4

The Story of Jesus, chapter 11

Christ in the New Testament, chapter 5

Comments are closed.